The Rinse-And-Repeat Strategy of Serial Acquirers

At the heart of compounding

Introduction

When searching for Compounding Tortoises, serial acquirers have proved to be a good starting pool for further screening. Coupled with organic growth, these vehicles can keep on growing at a double-digit clip, just by acquiring new companies.

The best serial acquirers are run by very competent management teams who prioritize entrepreneurship and corporate culture above short-term thinking. As their collection of subsidiaries grows, decentralization is the ultimate way of providing ever-lasting autonomy to the acquired entities. Therefore, serial acquirers don’t just have to be financially strong, but they should also have a durable cultural spirit that’s very hard to replicate.

As stated above, the process of finding attractive M&A targets is what gets the double-digit compounding flywheel going. In order to be successful, serial acquirers tend to pick defensive businesses with low capital intensity, a high internal ROIC, strong profitability and organic growth areas. Having a strong ROIC is precisely what we’ve explained in the prior article.

Contrary to private equity, serial acquirers are usually perpetual owners of businesses, so higher or lower interest rates do not interfere with an exit strategy (buying, upgrading and then selling a company) as they don’t have one.

Just a Math Equation

What’s the return on making acquisitions? Historically, serial acquirers paid roughly 7-8 times EBITA, that is deducting regular depreciation from the EBITDA. Based on a corporate tax rate of 20%, this translates into a 10% to an 11.4% un-levered ROI in year 1. Adding a 3-5% organic growth rate to that, the ROIC for M&A is typically between 14% to 16%.

Here’s where things get tricky: the assumption of a constant transaction multiple and organic growth rate won’t hold in the real world.

As serial acquirers become bigger and shift their focus to larger deals, the ROIC tends to drop. Stated differently, it becomes more “costly” to grow at the same relative rate year after year.

It’s not a guarantee that the entire NOPAT/recurring free cash flow before financial items will and/or can be deployed on acquisitions. Therefore, a serial acquirer should have an established database of potential targets and a seasoned M&A team to act swiftly in case numerous opportunities present themselves.

Organic growth rates tend to be highly correlated with the overall economic growth. A few years of economic stagnation or contraction are likely to impact our compounding assumptions.

Regarding the third element, it should be noted that the internal ROIC of the serial acquirer’s subsidiaries will determine the required cash outflow to achieve a certain organic growth rate.

Let’s say a serial acquirer has a 12% ROI on its acquisitions and a 40% organic ROIC. Ceteris paribus, 4% organic growth over one year requires 10% of the serial acquirer’s NOPAT to be reinvested in the business. The 90% leftover NOPAT is then allocated to M&A. Before any assumption on taking on external funding, the total shareholder ROIC is 4% (organic growth) plus 10.8% (90% x 12% ROI). If the serial acquirer were to distribute a dividend, it should not be added to the 14.8% simply because there’s no leftover NOPAT. Getting a dividend is offset by the increase in borrowing and thus reduction in the company’s intrinsic value.

Let’s now pencil 4% organic growth, 40% NOPAT allocation to M&A spending and a 50% cash dividend payout. The stock is trading at 25 times NOPAT. Due to a lower weighted ROIC on the company’s overall capital allocation strategy, the return picture worsens from 14.8% to 10.8% (4% + 4.8% + 2%). Still in the double-digit range, but things could go south quickly (flat or organic growth).

When analyzing a serial acquirer’s growth potential, we focus on five key elements:

business cyclicality

the current ROIC on acquisitions

the current ROIC on organic growth, and what the operating invested capital looks like (i.e. higher inventory level, more fixed assets?)

the current capital allocation mix

optionality

Due to supply chain constraints, inflation et cetera, optionality has become a mind-breaking topic over the past years. What if a serial acquirer’s ROIC deteriorates because of temporarily higher inventory levels, higher CAPEX spending (due to inflationary pressures) and subsequent cash drains leading to a subdued M&A activity? Will the lower ROIC be just transitory (a term central bankers familiarized us with), or could it structurally lower our forecasted terminal NOPAT and thus expected shareholder returns?

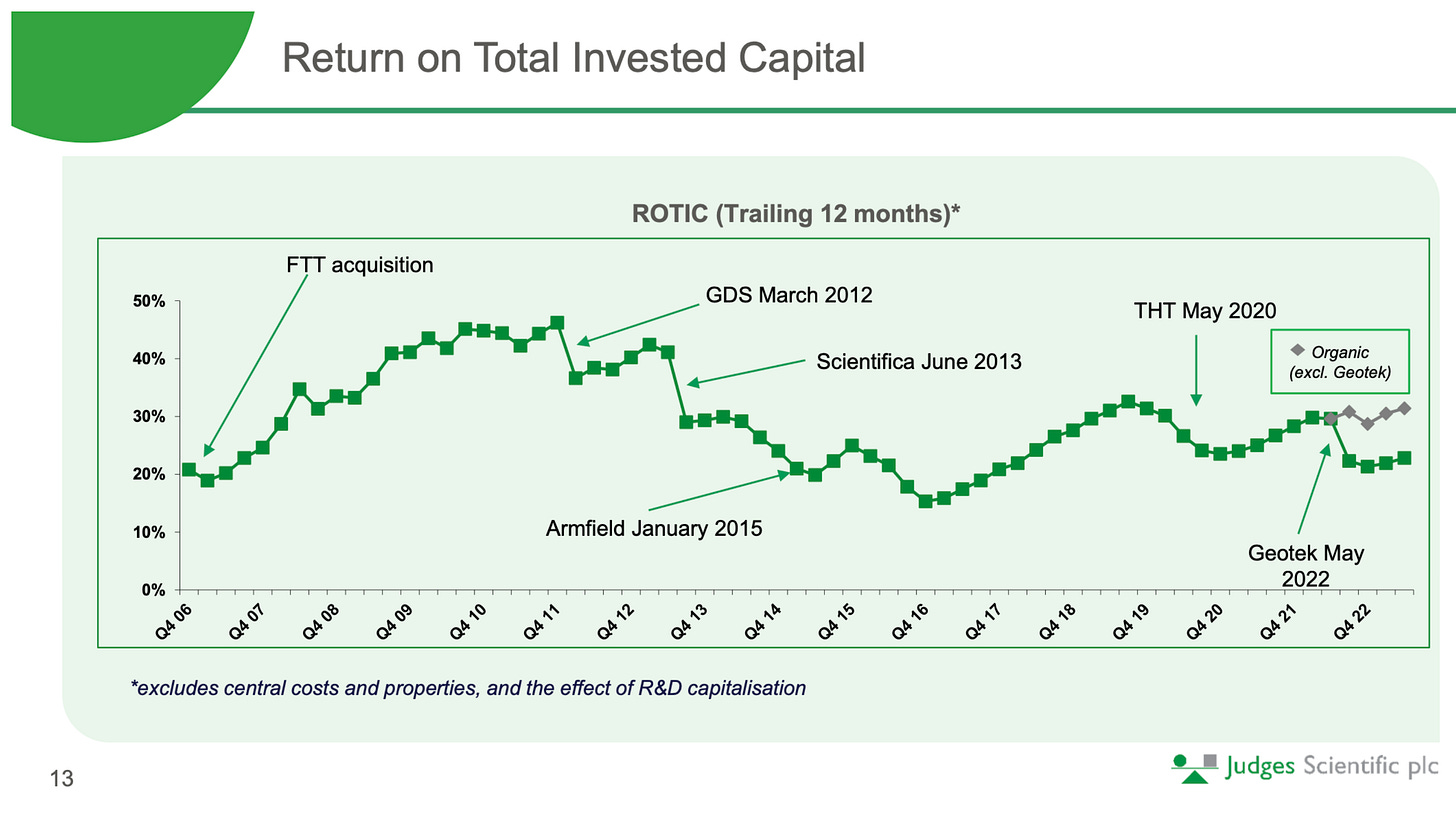

To Judges Scientific, peaks and troughs in ROIC are not uncommon. As this serial acquirer grew in size, larger deals evoked execution risk and led to some severe bear markets in its share price.

Today, organic ROIC is somewhat hampered by supply chain constraints and prudent inventory buildup should new macroeconomic disruptions emerge. Interestingly and when talking about optionality, a normalizing working capital situation is a clear plus to enhancing organic growth and thus future shareholder returns. That’s because organic growth will require less NOPAT to be absorbed by working capital requirements. This cash flow saver could be put to work in M&A or returned back to shareholders.

Thinking about optionality is a balancing act but a very rewarding one, as it forces us to unravel a business’ efficiency and risk profile. Investing in serial acquirers is - just like with any other investment - a matter of trust in management’s capabilities of delivering durable shareholder value creation. Even more so during uncertain times!

Don’t just take a management’s every word for granted. Don’t turn a blind eye to a shift in accounting policy (share-based compensation, treatment of lease liabilities), management complacency and fancy presentations that lack relevant content about the underlying business performance.

Prioritizing Profitability Over Revenue Growth

Whilst there are several ways to building out a successful serial acquirer, improving profitability is the easiest way to immediately enhancing shareholder returns; improving profitability requires little or no CAPEX.

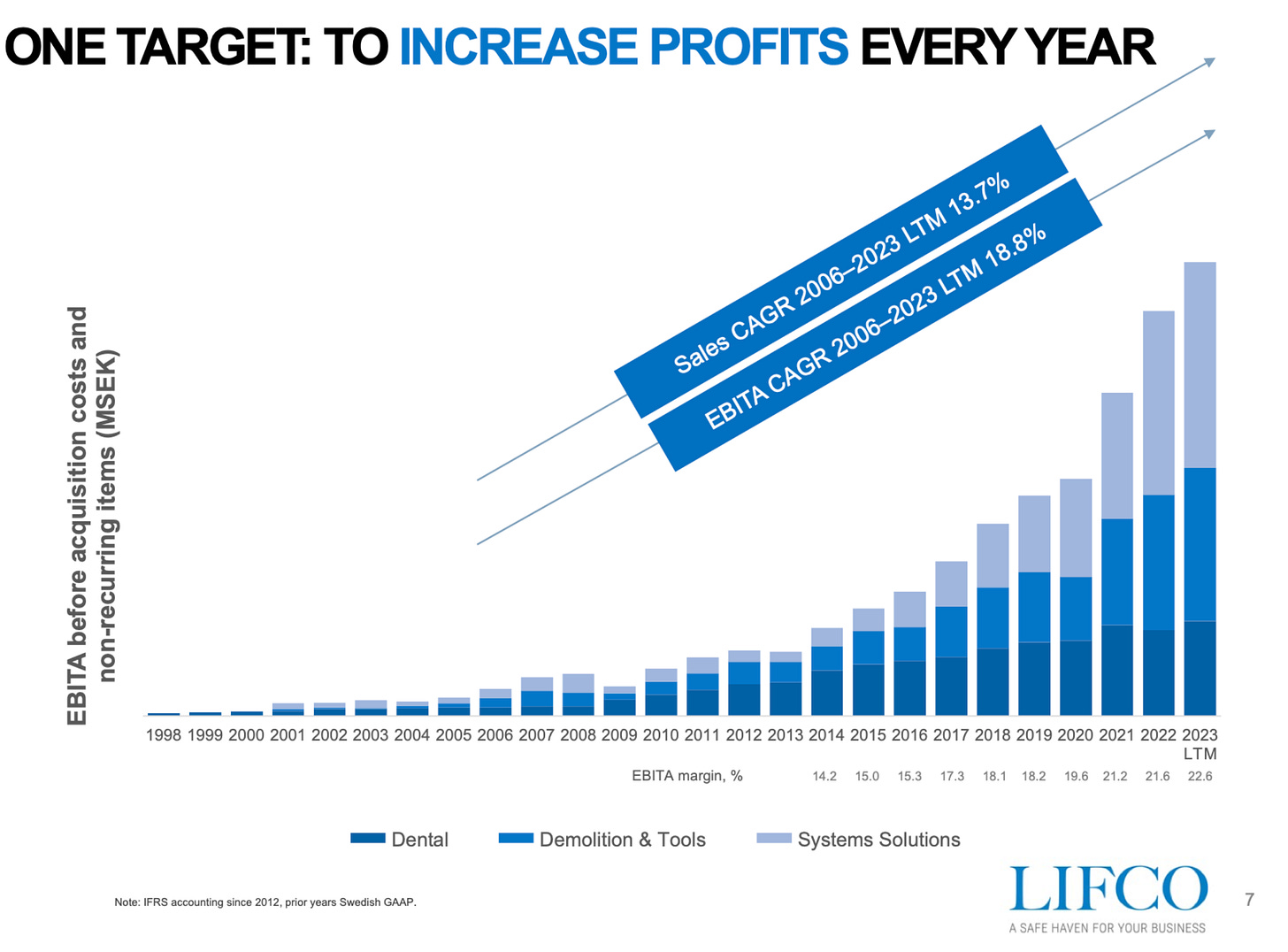

As for the Swedish Lifco, led by Per Waldemarson, it’s been an amazing run. Although it has typically been growing the top line by “just” 2 to 3% organically, revenue growth from acquisitions tends to be 8%.

However, it doesn’t end there: improving profitability has always been at the core of Lifco’s operating rhythm, and as you can conclude from the below graph, Lifco’s EBITA growth has been on steroids for several years now. Admittedly, we expect this annual tailwind to eventually level out.

As Fredrik Karlsson, the former CEO of Lifco and the current CEO and co-founder of another serial acquirer named Röko, once said:

We’ll have to convince all of our managers that margin is more important than growth. But naturally, people want to grow their business and become big. (paraphrased)

Profitability should translate into strong cash flow generation. In 2022, some serial acquirers struggled with keeping their cash from operations positive. One of them was Bufab AB. As a consequence of low cash conversion, the debt ratio rose considerably.

Carrying more debt than usual at a time of soaring interest rates stokes share price volatility. In hindsight, Bufab’s cut-in-half stock price created a nice buying opportunity. It depends on one’s risk personal tolerance to buy higher-leveraged serial acquirers, but we all should acknowledge that even the more defensive serial acquirers such as Lifco and Indutrade got punished over the course of 2022.

Operating with Negative Organic Invested Capital

So far, we’ve solely discussed serial acquirers that operate with positive organic invested capital (fixed asses such as buildings, machinery and short-to-mid-term working capital). There are exceptions to the rule, specifically software companies that benefit from deferred revenues.

For example, customers pay in advance for their one-year subscription and while that payment will be recognized as revenue gradually, it provides the software company with an immediate cash flow readily available to invest.

From a time value perspective, it’s undoubtedly a gift for growing businesses under a going concern scenario. As they grow, working capital becomes even more negative, which improves the liquidity position on top of their regular earnings visibility (i.e. recurring revenues).

One of these lesser-known software serial acquirers is Vitec AB, for which organic growth has so far been superior when compared to its direct peers. Additionally, profitability is rock-solid, as Vitec’s businesses continue to scale.

There’s one caveat in analyzing the income statement: the treatment of capitalized development costs under IFRS, given that they show up again in the cash flow statement as CAPEX. In the end, free cash flow and growth are the driver of shareholder value creation. The first question has to be: what portion of (capitalized) development costs is recurring?

Ignoring the effect of capitalized development costs on the income statement would lead to a considerable valuation discrepancy between the reported EV/EBITDA and adjusted EV/EBITDA. For your reference, the analyst consensus is calling for an 18.9x EV/BITDA, whereas the underlying figure should be more close to 28x (2024). A wholly different picture now!

Put/Call Considerations

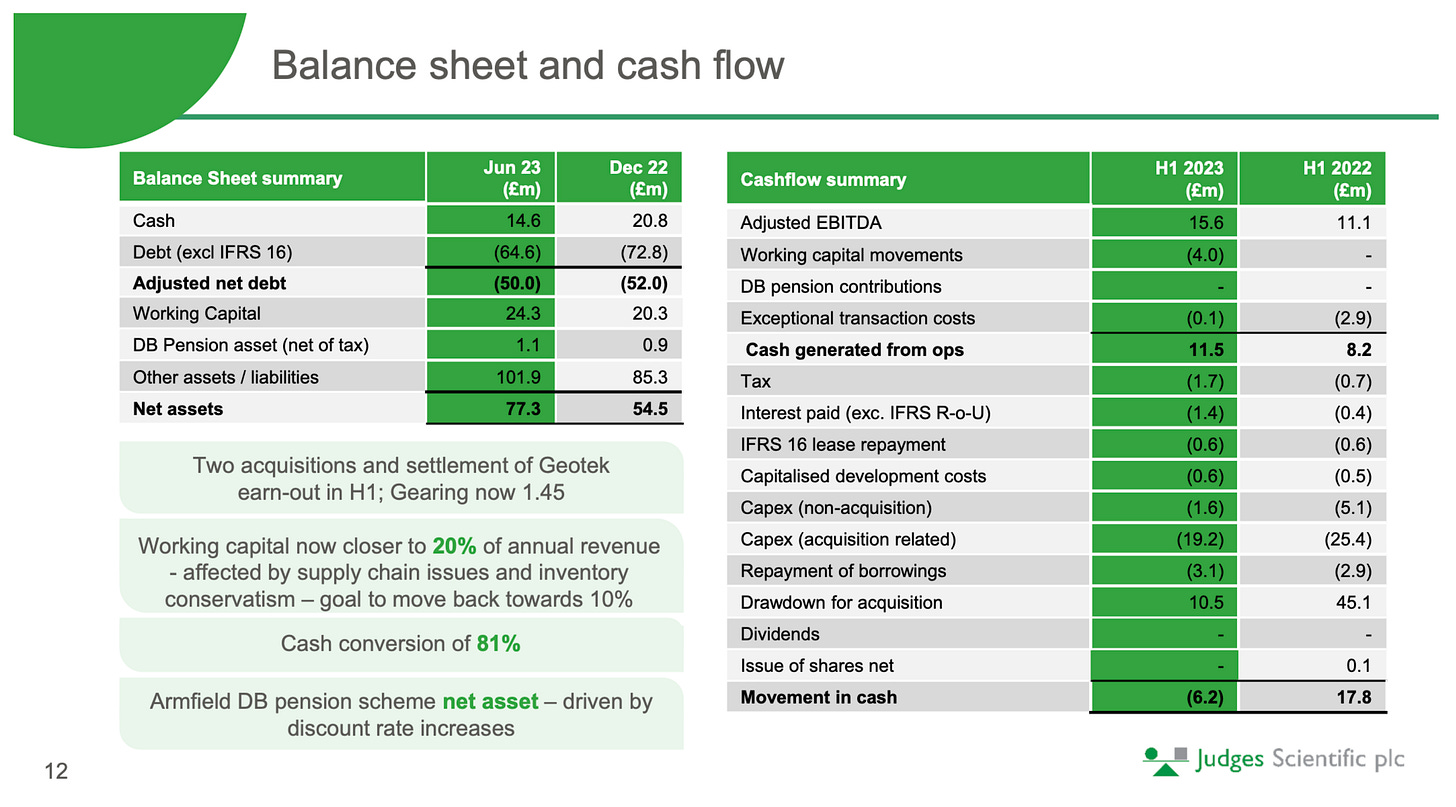

To round off this article, investors who want to dig deeper into the serial acquirers space should be cognizant of put-call debt and/or contingent earn-out liabilities. Most of the time these factors are excluded from the net debt figures. Still, they can be very material in assessing future net cash movements.

Negative put-call revaluations (i.e. a higher future cash outflow for the acquirer in case the minority shareholder(s) would decide to sell their remaining stake) indicate the acquired subsidiaries have performed better than expected. Even though the adjusted debt figure will worsen, the revaluation should be viewed as a positive.

If you found this article useful, then please give it thumbs up.