Valuing Quality Growth Companies

Why we prefer NOPAT over Free Cash Flow (FCF), and how to calculate it for quality growth companies

Hi fellow Tortoise!

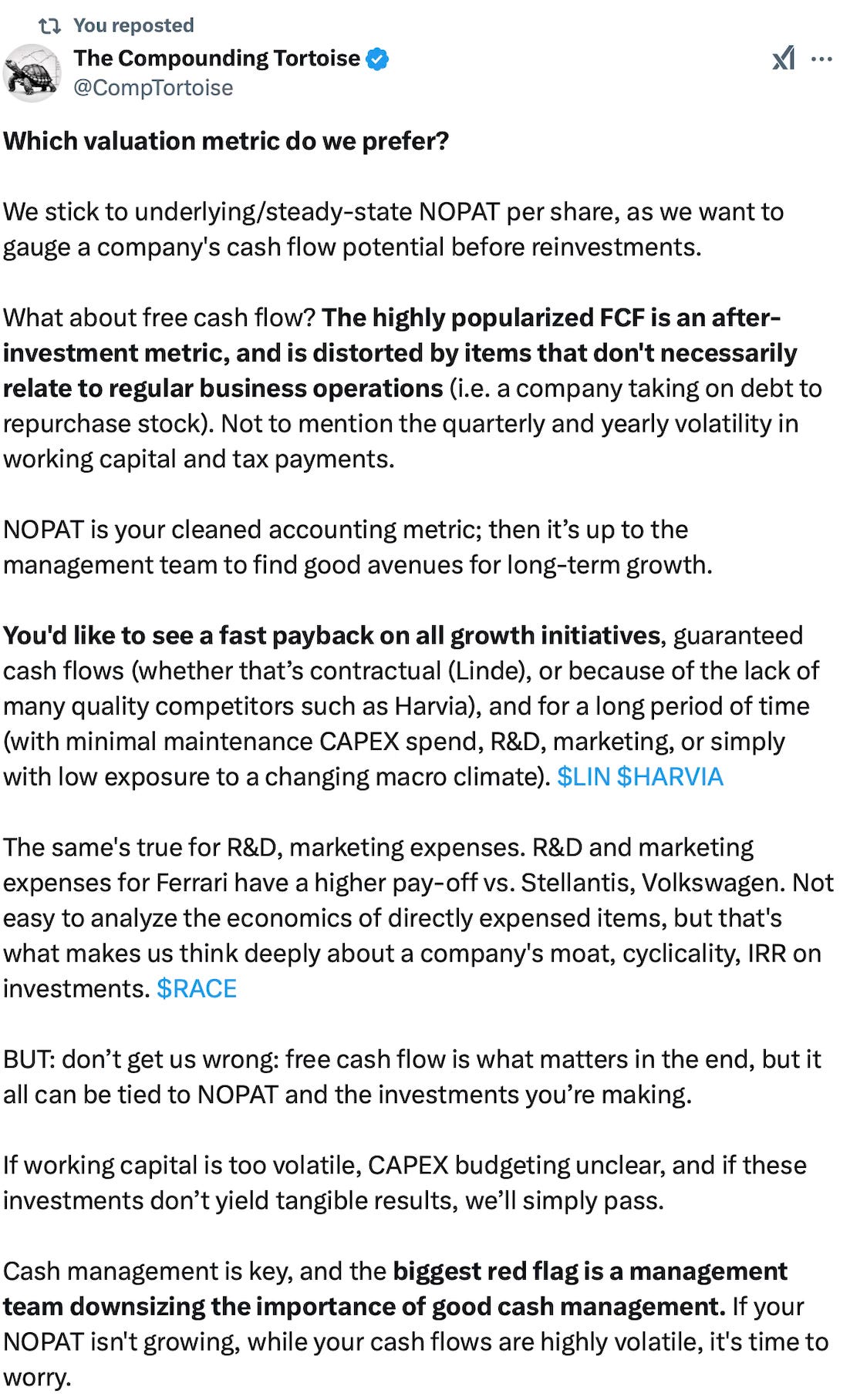

From time to time, we receive quite a bit of questions on how to value quality companies, and how to gauge the economic returns of capital allocation. While valuation is a subjective topic, we stick to our favorite metric, namely steady-state NOPAT. In fact, we tweeted about it earlier today.

Free cash flow is an after-investment metric, which would severely penalize good companies investing at returns exceeding their cost of capital. A low free cash flow yield would also make comparisons to the risk-free rate meaningless.

As we explain in this week’s bi-weekly webinar, we view steady-state NOPAT as the pile of cash a company would have if it 1) stopped reinvesting for future growth, and 2) made only maintenance investments, both in physical assets (machinery, factories, leased assets (lease repayments) and intangibles (IT, capitalized R&D). Think of it like a fixed coupon you’re getting from fixed income investments.

Of course, we don’t want to own stagnating businesses, but it paints a good picture of what a company retains in free cash flow before pursuing discretionary/growth spending. All cash flow that’s left for share repurchases, repaying debt, paying out dividends is your final free cash flow.

Put another way, if you’re growing slowly with a lot of capital spending, it’s worrisome. Then, your low free cash flow is indicative of poor returns. The same’s true for inconsistent spending, as it complicates proper modeling. If you’re growing nicely (12-15%) and still retain 50% of your pre-growth free cash flow, then we’re getting excited.

Gauging the economic returns on capital allocation should be viewed over a multi-year time span, as for instance changes in working capital due to external factors (i.e. post-COVID disruptions) would make you jump to overly positive or negative conclusions.

And so it happens that quality growth companies are worth a lot more than what their current P/E, FCF Yield suggests… as growth investments depress their reported earnings and FCFs. That’s true for Ferrari too, the company we’ve used to illustrate our thinking on a company’s longevity and underlying valuation.

The presentation can be watched below, including the slides and the transcript.