Finding Excellent Capital Allocators

Understanding and measuring what drives true value creation

Early June, we shared a blog with the 10 key takeaways from the TIP interview with Tim Koller, who co-authored McKinsey’s Valuation Book. It’s our most-read blog to date.

Today, we’ll be covering a recent follow-up interview during which Koller highlighted the facets of capital allocation and how mainstream some of wrong concepts have become (e.g., a strategy that’s focused on continuous margin expansion won’t necessarily produce the highest economic value).

Talking against our own playbook of stock-picking, it’s worth remembering that Hendrik Bessembinder’s study on stock market returns concluded that the average stock investor is unlikely to outperform short-term investments such as U.S. Treasury bills. Only a small number of stocks perform exceptionally well and generate the majority of the returns in the stock market. That outperformance is driven by capital allocation, as ROIIC, true cash IRRs, reinvestment rate, and longevity drive shareholder value creation. Put another way, a select group of management teams do extremely well, making up for all failures and average performance of others.

How should we think about a company’ excess cash allocation strategy? What about the timing of investments? Why should we question a company’s total ROIC and look for disaggregation instead? We’ll address these questions with some practical examples (including serial acquirers).

Share this latest blog with your network – it's freely available to all.

Other material you might want to check out:

How valuation, ROIIC, and durability are all connected to each other.

Last Friday, we published the key lessons from Chris Hohn, and it once again led to significant reader traffic. Hence, we’ll keep doing more of these series, while shedding our own light on how we approach concentrated enhanced quality growth investing.

1️⃣ Excess Cash - Now What?

Kicking at an open door: high return companies will eventually become flush with cash as exceptional growth isn’t sustainable. By exceptional, we mean 20-30% or more and with growth being funded internally. You could imagine a case where frequent equity raises allow you to grow strongly (with total growth exceeding the ROIIC), just as long as shareholders are willing to fund your growth strategy.

It's not inherently a negative sign if a company, particularly one with a high return on capital and moderate growth (e.g., mid-single digits), generates significant cash flow beyond its operational needs. In such scenarios, if the core business doesn't offer enough opportunities for substantially faster growth, pursuing unrelated ventures often leads to poor outcomes.

Buybacks have been a popular way of returning cash to shareholders:

First of all a lot of share buybacks are concentrated in a small number of companies/industries. If you look at it, these are typically companies or industries like certain tech, life science, consumer product companies etc. These are companies that generate a lot of cash flow and there just aren't enough opportunities for them to deploy all that cash flow. - Tim Koller

He acknowledges that some companies may engage in buybacks for short-term EPS manipulation, which he doesn't advocate, but emphasizes that for highly successful, cash-generating companies, it's often a pragmatic decision given the lack of sufficient profitable reinvestment avenues.

He also talked about three examples where moving outside the core circle of competence and/or believing other alternatives would provide incremental shareholder value failed greatly.

A large sanctioned company that destroyed capital by investing in unrelated businesses (hotels, gas stations, cinemas) because it couldn't move cash out of the country;

US utility companies in the 70s and 80s, and oil companies in the early 80s, which failed when they diversified into non-core areas like insurance, department stores, or computers.

Speaking of today’s energy transformation, an oil and gas company might have an advantage in carbon capture due to existing infrastructure, but likely not in building wind or solar farms, as these require different skill sets. The central message is that diversification outside the core business should only occur if the company genuinely brings a unique competitive edge.

This sort of leads into a discussion around serial acquirers and whether or not they’d better be sector-focused or just buying whatever they can. When you’re sector-agnostic, you can cater wider nets, implying a much longer runway. Conversely, Constellation Software (the leading VMS serial acquirer with a lot of recurring revenues) has managed to replicate its M&A playbook for many tiny deals, with the low-hanging fruit being pricing.

In March 2024, Fredrik Karlsson (CEO and co-founder of Röko AB, which IPOed earlier this year) commented on the sector-agnostic acquisition strategy:

The temptation when you’re a successful serial acquirer is to think: does this work in any sector? The temptation for speed by lowering the quality requirements. It was interesting what Storskogen did: buying anything they could possibly find in several sectors. I wasn’t sure they would run into problems. There’s a limit to how bad quality you can buy and still be successful.

Some investors have been vocal about Röko being similar to Teqnion: buying companies with no clear moat, difficulty in maintaining that decentralized model when the cycle’s challenging… Many leaders pride themselves on their decentralizing spending authority during prosperous periods.

As of today, we find it highly difficult to believe Röko is the next Teqnion. First off, Röko’s got a real CFO (Johan Bladh), while Teqnion has cycled through CFOs like football coaches and currently lacks a formal one. Financially, Teqnion's free cash flow generation, underlying profitability, and organic growth are simply inferior to Röko's.

Just to illustrate: in Q2, Teqnion’s reported EBITA grew thanks to … a significant positive revaluation of earn-out liabilities (23.6m SEK). In other words, a reduction in the expected payout to previous business owners. Keep in mind that earn-out revaluations don’t affect the goodwill figure, so there’s no additional impairment (that would be double-counting).

Bullish investors could argue: if and when the cycle turns, it’s likely that Teqnion then has acquired companies at much more compelling forward valuations/IRRs. The reality is that consistency, cash flow, profitability, and organic growth from day 1 post-acquisition are much more valuable. We’ve illustrated the importance of consistency in our Diploma deep dive (more on that later). Unless you can perfectly time a business turnaround, we’re better off holding consistent winners.

2️⃣ You Need Some Centralization & Backing the Right People

Tim Koller called out that the key hallmark of good leaders is their granular involvement in decision-making. They are close enough to individual investment decisions, often making them personally, rather than fully delegating to lower-level division heads. The CEO, often in conjunction with the CFO and other top executives, possesses the enterprise-wide perspective necessary to strategically move resources across different divisions and ensure long-term growth investments.

A concrete example would be Constellation Software. While it’s all into decentralization, you simply can’t sit back and let lower-level managers make all capital allocation decisions without questioning these. As Mark Miller said last May during the AGM:

Again, if I'm talking about a business, not a portfolio. And the last thing you'd want to do would be ship the capital. But if you've got the wrong leader in that business or a leader who you don't feel is going to patiently and rationally make good decisions around either organic growth or acquiring businesses, you'd much rather have that cash back and put it somewhere else.

Therefore, a robust system should be in place where the CEO makes critical decisions regarding investment in growth, strategic projects, and project termination. For CEOs and CFOs, dedicating sufficient time to resource allocation is paramount, as it's one of the most crucial aspects of their role, alongside talent management, in driving significant impact within large organizations. A failure to prioritize this time directly leads to suboptimal resource allocation.

Related to this, is that when projects failed, understanding the driver of failure is vital for learning and for avoiding unfairly penalizing individuals, which could discourage them from taking on risky but potentially rewarding projects. Ideally, management teams should be rewarding individuals who proactively kill projects that aren't working out, even if they've already invested time and resources. This encourages faster failure, resource reallocation, and fosters a culture of learning from noble failures.

3️⃣ Focus On Incremental Economic Value Creation

For quite some time, Tim Koller has strongly critiqued the widespread CEO/CFO mandate for every business to improve their margins. He gave an example of a profitable business unit (30% margins, 45% return on capital) passing up new growth opportunities with 25% profit margins simply to meet such a universal edict.

He also expresses concern when companies publicly state they'll grow profits faster than revenues, as this is mathematically unsustainable long-term. While initial cost-cutting can be beneficial in fat companies, after three to four years, it often leads to detrimental cuts in growth-related investments like product development, marketing, and sales. This underinvestment eventually harms the company's competitive standing.

I've seen companies that have had to you know acknowledge that they've underinvested and and they would say something like we have to reset our business because we have underinvested relative to our peers, because we've grown our profits so fast relative to our revenues and the way we've done it is by cutting investments for growth, right. - Tim Koller

Markets may initially reward short-term profit growth, but eventually, the negative impact of neglected investments becomes apparent. In industries where customer experience is central to a company’s pricing and growth strategy, cutting back on discretionary spending that’s in fact necessary will erode your market share.

Another common pitfall is where division heads, focused on short-term performance, might reduce investment in growing businesses to compensate for underperforming units, which ultimately harms the company's long-term prospects. If costs are cut, the savings should be reinvested into growth opportunities elsewhere in the business. A crucial consideration for cost-cutting is whether it will be noticed by the customer. Efficient distribution or back-office cost reductions are good, but cutting corners on material quality or customer service will eventually lead to customer dissatisfaction and brand damage, unless the explicit strategy is to target a lower-quality market segment.

Now, very few companies will disclose the returns on incremental invested capital, or segment analysis. Therefore, calculating ROIC and ROIIC requires somewhat subjective analysis when modeling a company’s future growth and required investments.

We cannot always perfectly estimate what’s been driving recent NOPAT growth: is it because of prior years’ investments? Is it because of pricing tailwind affecting the base business? Is it because of economies of scale thanks to recent investments? We’ve come to accept that it’s all about being directionally right than precisely wrong.

4️⃣ Absolute Cyclicality - Overspending At Peak ROIICs

As you know, we’re not looking to invest in companies with absolute cyclicality, i.e., negative or positive growth (barring exceptional circumstances such as COVID-18 with pent-up demand in several sectors).

A major challenge in cyclical industries (like chemicals) is that companies tend to build new capacity simultaneously during good times. This leads to an oversupply that crashes prices and creates a bad cycle, leading to poor cash IRRs over the whole cycle. In that case, Koller advocates for a counter-cyclical approach, where companies invest when others are not, allowing their new capacity to come online during more favorable market conditions.

Part of the problem there when I discuss this with chemical company executives: it's easier to get permission from the board to build a new capacity when you know everything is going well, but that's not the right time to spend it.

This requires a disciplined CEO with an independent point of view, someone willing to defy conventional wisdom, much like Warren Buffett. Such leaders analyze and time their capital expenditures strategically, rather than following the herd. The key takeaway is that strategic capital allocation often involves the challenging decision of not making an investment when market conditions are unfavorable, or investing when others are pulling back.

When it comes to CAPEX-heavy cyclicals, many companies sometimes defer plant maintenance to boost short-term earnings, risking inefficient operations and unplanned outages, despite the need for regular upkeep. So-called midlife refurbishments require 5-10 years of advance planning due to long asset lifecycles and the need for backup capacity. Getting this planning wrong has severe, long-term consequences, unlike industries where investment cycles are shorter.

5️⃣ Relative Cyclicality - Timing of Reinvestments, ROIIC, and IRR

In our previous discussions, we've highlighted that a company's growth hinges significantly on the timing of its reinvestments, whether these are channeled into marketing, sales, R&D, capacity expansion, working capital, or M&A.

A less frequently discussed aspect is that lower ROIIC companies (those in the 10-15% range) take considerably longer to generate strong cash IRRs compared to businesses with much shorter payback periods (like Harvia's organic growth investments). Furthermore, these lower-ROIIC companies must deploy more capital to fuel their growth, which amplifies the impact of timing and external challenges such as supply chain disruptions or a slower M&A environment. High return companies (>25% ROIIC) need fewer reinvestments. As such, they’re less prone to timing risk.

Consider retailers like O'Reilly and AutoZone as they open new stores. The cumulative return on capital for a store that's been open for 10 years far surpasses that of a 1-year-old store. So, how do we account for their ROIC and ROIIC?

It's a positive that these two retailers have been consistently reinvesting in their businesses (through ordinary capital expenditures and/or leases) for several years, even decades. This means that even as they invest in new stores and add incremental invested capital, they still benefit from the scaling and leveraging effects of their earlier store openings. In simpler terms, any dilution in NOPAT from recent investments is offset by the traction gained from previous initiatives. Consequently, relying on ROIIC for modeling growth and the associated reinvestment remains valid for companies with a continuous stream of reinvestments that share the same return economics.

However, the picture becomes more ambiguous for serial acquirers, primarily because their acquisition mix cannot be reliably extrapolated into the future. This is especially true given the recent period of heightened inflation and extraordinary margin expansion. For instance, if you were to analyze the IRRs from Lifco's M&A activity across different cohorts (e.g., 2020, 2021, 2024), you'd observe significant variability. While some degree of fluctuation is normal, it also underscores the need for individual acquisition analysis (where feasible) to truly ascertain if a deal is accretive.

The main drawback of using rolling ROIC is that it disregards longevity. A company reporting a 20% ROIC today doesn't tell us much about the intrinsic annualized cash returns on future incremental investments, nor how long these returns will persist. It's akin to stating your total return on stock X is 50%. If that return took 15 years to generate, the annualized outcome would be quite disappointing.

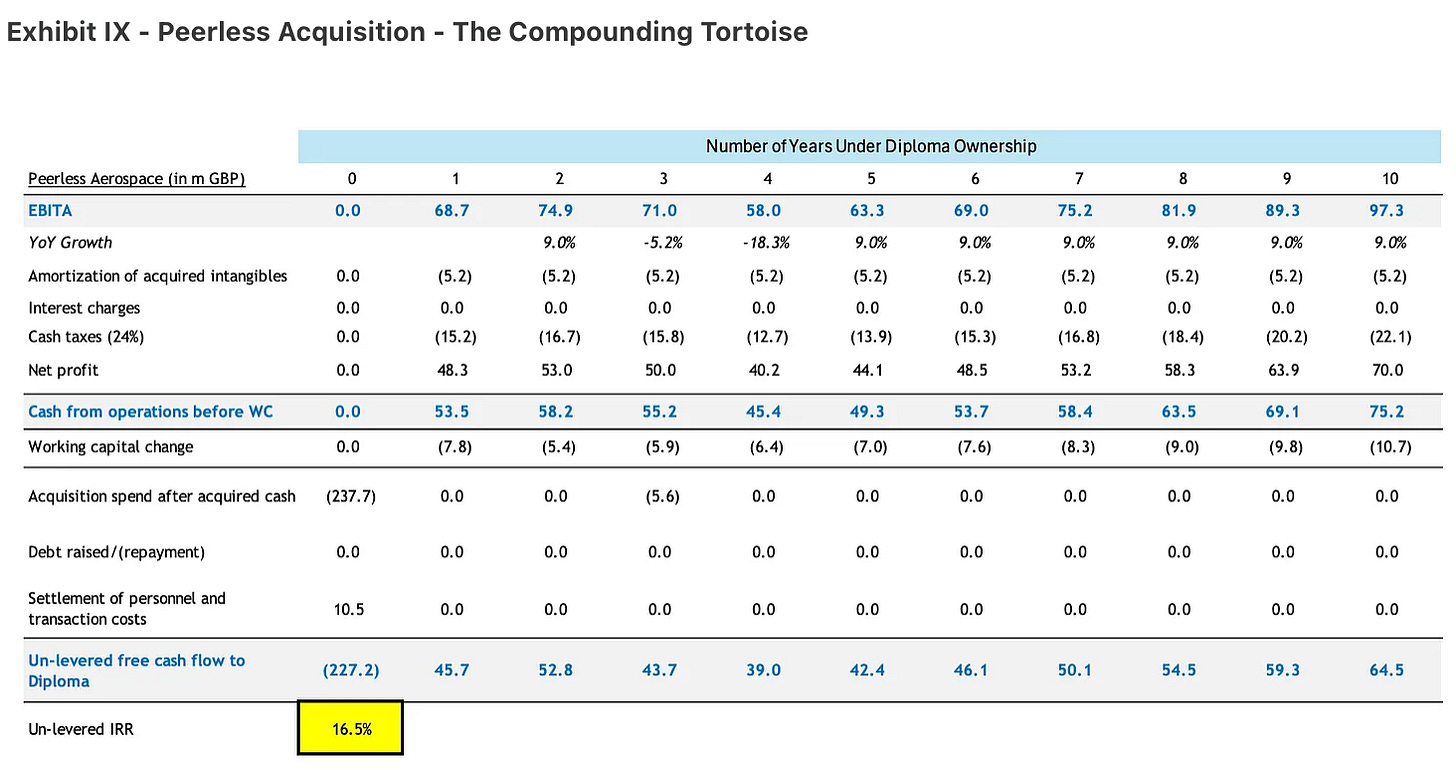

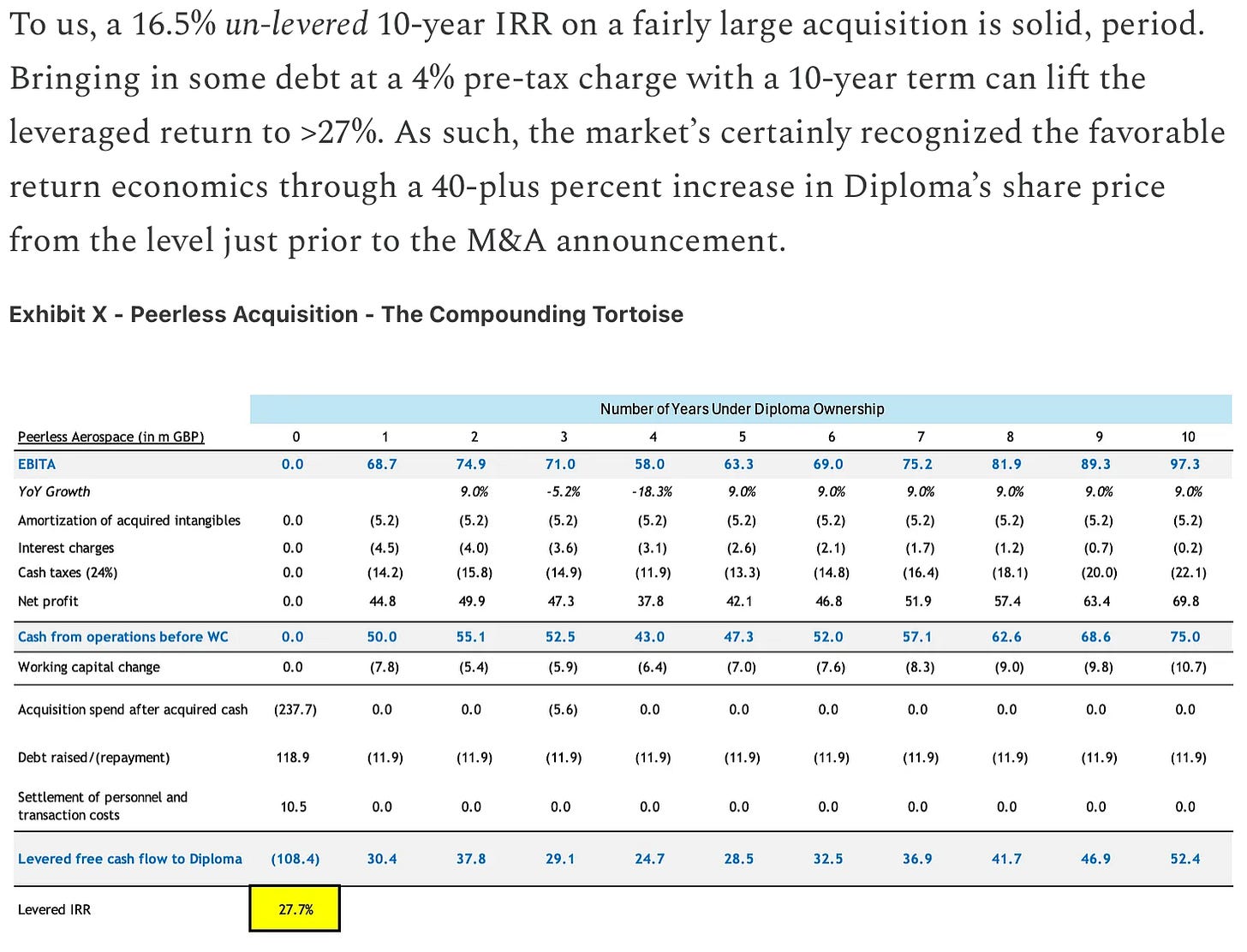

Therefore, we need more context. Diploma, the UK-based serial acquirer, serves as a good example. Last week, it released a robust Q3 update, further upgrading its full-year outlook with 10% organic growth and an unchanged 22% operating margin. In Q3, Diploma delivered an impressive 12% organic growth, propelled by a strong rebound in Seals and the continued impressive growth of Peerless. In our in-depth analysis, conducted before the Q3 report, we explored the potential IRR on the Peerless Aerospace acquisition.

You might ask: shouldn’t we include an exit value to better reflect the IRR? Our two cents on this:

Assuming Diploma were to divest Peerless by the end of the 10th year, the IRR would have been even higher. However, this would necessitate a search for a new acquisition target, a process that is inherently time-consuming. Diploma typically prefers to hold businesses perpetually, especially one the size of Peerless.

The IRRs are less impacted by the exit cash flow as we extend the horizon. That’s quite logical: the future discounted value of cash flow by the 10th year is higher than that in the 20th year.

Now, following the Q3 report, it turns out the picture for Peerless is even better… we now estimate that the acquisition is on track to deliver a >20% un-levered cash IRR over the first 10 years. That’s truly exceptional for an industrial serial acquirer completing such fairly large deal (300m USD).

Interestingly, Chris Davies, CFO at Diploma Plc mentioned in November 2023:

On Windy City (Wire), I need to be careful I've only been here a year. Windy City is probably one of the best businesses I've ever seen.

Windy City Wire has indeed been a great acquisition too, but Peerless shoots out the lights.

The reason we’re bringing this up is because time is an underrated concept in finance and investing. When allocating capital, the IRRs on each project should be analyzed, as well as the associated risks.

Conclusions

To wrap, we’d say great capital allocators focus on:

Cash IRRs and payback times. A rolling ROIC tells us very little about what lies ahead for a company. ROIC is distorted by inflation, any changes in depreciation policy. You can have a growing ROIC with flat profits, because you’re not reinvesting in the business, or because of disproportional pricing tailwinds.

Set of realistic expectations;

Consistent reinvestment runway;

Individual projects’ IRRs that exceed the hurdle rate;

Incremental returns instead of rolling accounting metrics;

Their circle of competence where there’s a clear competitive edge;

Margin of safety to generate high returns, irrespective of the macro climate;

Being transparent about mistakes and learning from failures;

Longevity, i.e., earning high returns for as long as possible with very little maintenance investments (whether it be CAPEX or directly expensed costs).

When reflecting on these criteria, the pool of truly excellent companies is very limited.

Enjoyed this one a lot. Any thoughts on Diplom's dilution?