Intrigued by Drawdowns

Charlie Munger's "Acknowledging what you don’t know is the dawning of wisdom"

Last month, we published a blog on the Art of (Not) Selling - Makings of a Multibagger, touching on skin in the game, and why even predictable businesses can experience huge drawdowns in their share price.

It’s always been a intriguing concept: why do stocks have periods of severe drawdowns, and even though the theory is to sit tight on the right businesses, the average retail investor ends up losing money in real terms.

Trying to get a very good sense of where things will be heading over time (e.g., this will be a much better business over time with decent growth, and it’s now trading at a reasonable multiple), quality growth investors must embrace uncertainty. You simply can’t say where a stock will be trading over the next few months, quarters, or even years. It can be dead money for several years and then quickly catch up with past years’ earnings growth and improvement in return on capital.

Over the years, we’ve evolved from calculating supposed fair values to buying excellent business that exceed our hurdle rate and understanding the embedded optionality for our companies to potentially beat our longer-term expectations.

Meanwhile, we have no clue whether a projected annualized return of 12% will be evenly distributed, very back-end loaded or front-end loaded. Simply put, let the market surprise and beat you: you can’t time, and even insiders/managers should better not trade around their positions for the short run. If they do, it’s usually a very bad sign.

Letting the market beat you essentially means that you must accept periods of significant relative underperformance (which we’ve become comfortable with given the type of companies we own).

Our buddy

sent out a spot-on blog last week, it’s compulsory reading in our view.In this brief blog, we’d like to shed some light on a couple of aspects as it relates to drawdowns:

They’re part of the game;

Transferring wealth from the impatient to the patient investor;

The impact of a low free float

They’re Part of the Game

Even though we know we’ll face significant drawdowns in our portfolio, it’s always a surprise to see them occur. Severe drawdowns are normal even for high-performing stocks with predictable growth and cash flows, and high-profile investors such as Peter Lynch whose Magellan Fund experienced four severe drawdowns, including a 42% drop in 1987. The ability to remain calm and hold a stock through these declines is a key competitive advantage that can lead to outperformance.

Charlie Munger said it beautifully:

I think it's in the nature of long-term shareholding with the normal vicissitudes in worldly outcomes and in markets that the long-term holder has his quoted value of his stock go down by say 50 percent. In fact, you can argue that if you’re not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50 percent 2 or 3 times a century, you’re not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you are going to get - compared to the people who do have the temperament who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.

He not only argues that you have to be calm about these declines, he goes further to suggest that if you cannot deal with them “you deserve the mediocre result you are going to get”. In other words, big drawdowns are a price to pay for superior long-term investment returns.

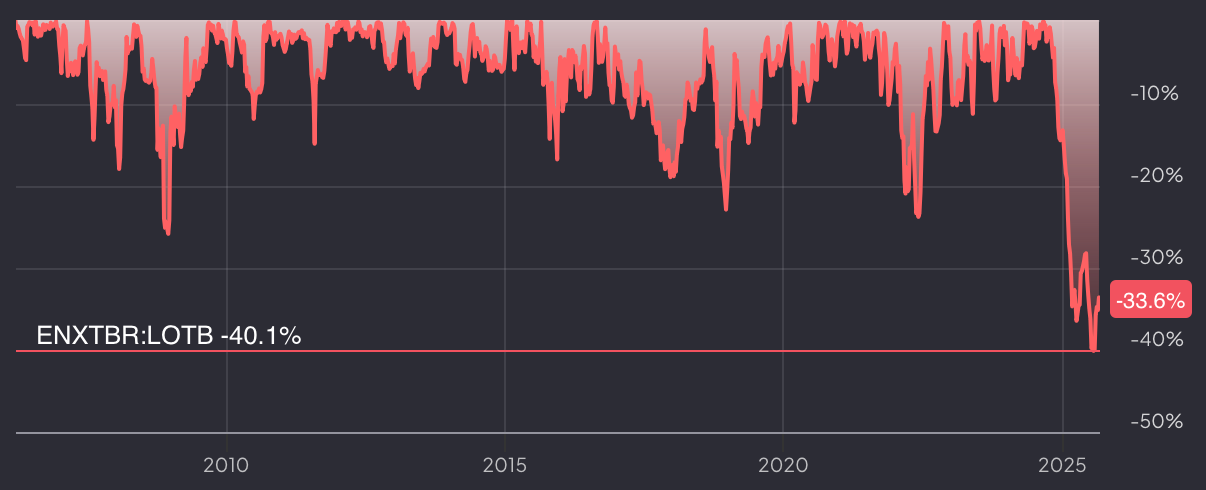

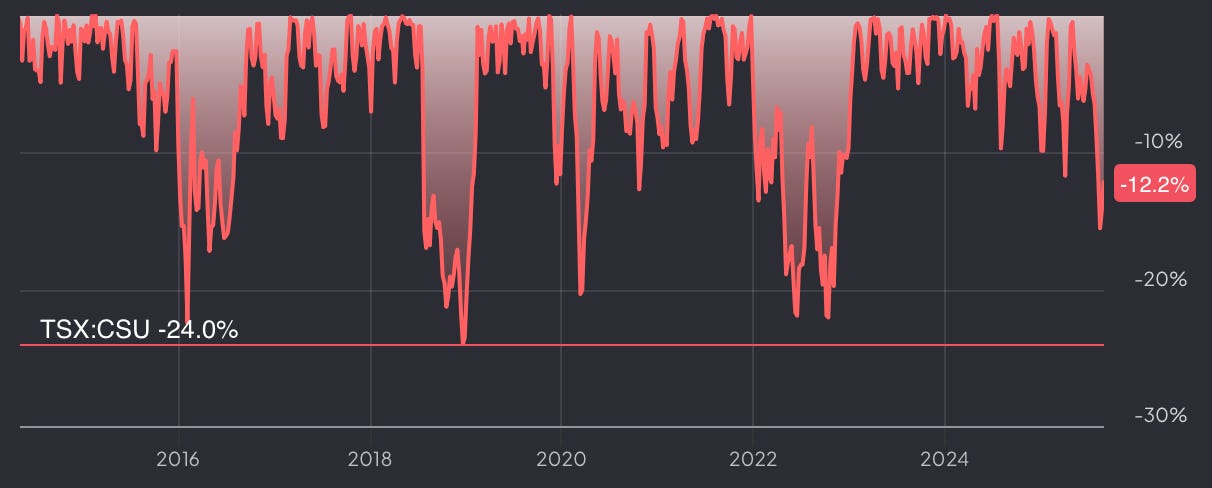

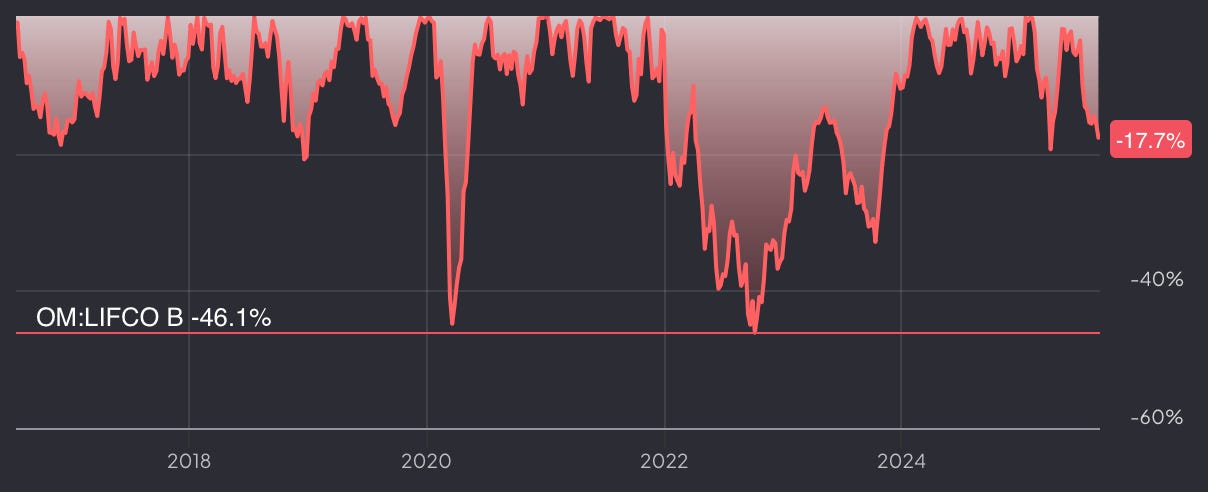

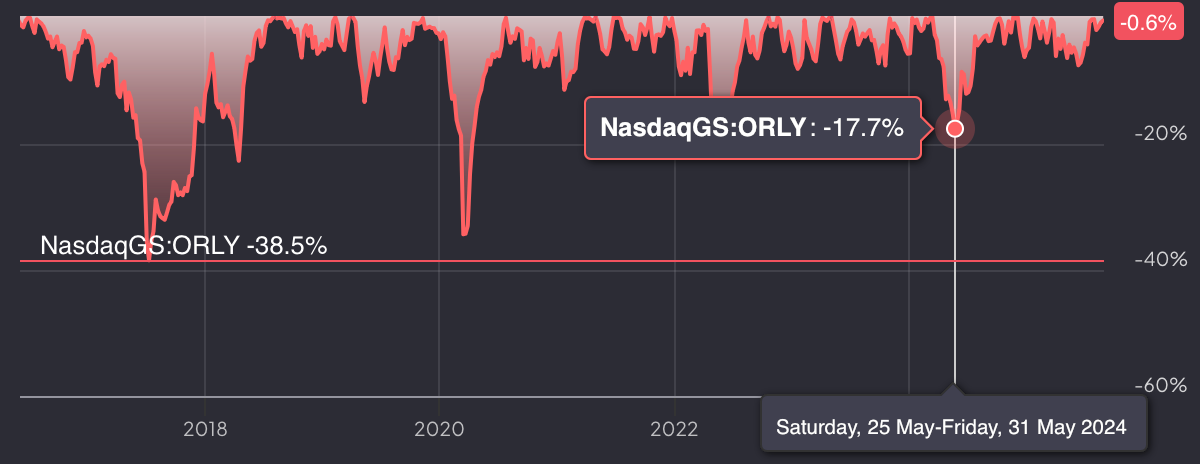

A couple of examples to illustrate how frequent these drawdowns are for some of the world’s steadiest compounders. Steady in the sense that their growth in revenues, NOPAT, and recurring cash flow has been like clockwork. Drawdowns of 8% - 10% come and go, while 20% - 25% happens every two/three years.

Late May 2024, several premium members were asking: why are you overweight O’Reilly and AutoZone, because they’ve been lagging the market? Today, the pendulum’s shifted completely as they’re trading at all-time highs (up 50% since May 2024).

Recently, the dip in Ferrari’s stock price was attributed to fears around its EV strategy, cancellations and what not. Shares have rebounded since the Q2 earnings report, making some wonder: why haven’t you added more on that dip? Today, the shares got upgraded by Deutsche Bank on the positive F80 supercar catalyst. Sentiment changes quickly.

On a related note, the recent share price outperformance for LVMH versus Hermès: what’s happening at Hermès that makes the stock underperform? Simply too hard to come up with a valid reason, and if there isn’t one, we shouldn’t break our head over it. The other point: if you’re that worried about relative performance, then why are you even a stock-picker?

Transferring Wealth from the Impatient to the Patient Investor

What remains so fascinating about some of the world’s best compounders is that sentiment and momentum lead to short-term decision-making. This means that, although these companies’ share prices have increased a lot over the past 7-10 years, how many shareholders were able to capture those 20-30% CAGRs?

A very simple example to illustrate this. You’ve got three short-term players and a long-term investor.

Player 1 buys at $10 and sells at $15 (profit of $5).

Player 2 buys at $15 and sells at $25 (profit of $10).

Player 3 buys at $25 and sells at $50 (profit of $25).

The total profit for these three players is $5 + $10 + $25 = $40.

However, a single long-term investor who bought at $10 and held until the stock reached $50 would have a profit of $40.

In this specific, simplified case, the total wealth created ($40) was distributed among three people. But what happens if the stock keeps going up to $100? The long-term investor's profit becomes $90, while the short-term traders have already cashed out and moved on, missing out on that additional value creation.

This demonstrates a key principle: each time a stock price rises, it creates an opportunity for incremental gains. The person who holds the stock for the longest period captures the most of that value creation. The smaller, short-term profits are just pieces of the much larger pie that is created over time.

Additionally, the longer you’ve been holding a stock that’s been going up, the better you should be able to handle drawdowns. You’ve seen the business grow stronger, and you’ve become accustomed to the weekly, monthly, yearly volatility.

It’s just simple math and logic, but difficult to implement in practice.

Low Free Float

Another thing to keep in mind is that drawdowns tend to be amplified by low free float. If you’ve got significant shareholder concentration, then share price volatility cuts both ways, creating an even bigger challenge for those who’re looking for “guaranteed” short- to mid-term returns.

Of course, if you’re invested in a company with like-minded long-term wealthy people/investment companies, it’s a good thing: you’re being surrounded by intrinsic shareholders.

Last week’s deep dive into Lotus Bakeries was one of the easiest write-ups we’ve published so far: steady compounding, long-term growth potential, growing incremental returns on capital. 50% of the shares are being held by the founding family.

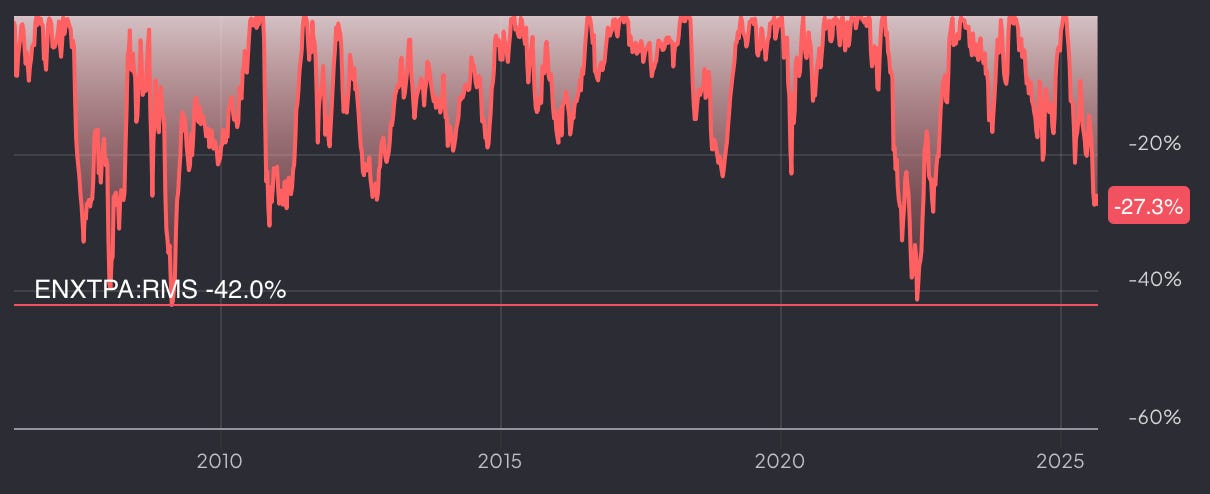

The stock's dropped by 42% in 9 months - that's pretty insane. Of course, it was highly priced late last year (around a 2% forward 10-year CAGR), but still. We think Lotus is the perfect example of why drawdowns are so intriguing. They can simply catch you by complete surprise. Compared to last year, little’s changed about Lotus’ growth algo, yet the stock price would suggest otherwise. It’s so bizarre that it makes you wonder: how can one make money?

Another example of decreasing free float is Harvia. Compared to late July, virtually all of Harvia's 100 largest shareholders bought the dip during August, increasing their combined position by c. 322,000 shares. That’s the biggest one-month increase since the fall of 2022. This implies that 76.2% of the shares are now being held by the 100 largest shareholders. Quite telling statistic: 98.3% of the known shareholders own less than 1,000 shares, averaging 798 units.

Interestingly, the 100 largest shareholders significantly reduced their combined allocation late 2021, at all-time high prices. Their total shareholding dropped to 64% of the total float (down from 75% at the end of 2020). Who bought these shares throughout 2021? Smaller retail investors. Who’s been selling out since? Smaller retail investors.

So, if you own this name, it feels like all future drawdowns will be self-inflicted: you should have known ahead of time that the most active shareholders are the emotional small retail investors, driving significant volatility.

We don’t mind this year’s and past years’ volatility. Being contrarian, you could say: well, the more it drops, the more we buy at higher forward returns (ceteris paribus). Whenever we have excess cash available, we look to top up our high-conviction positions at attractive forward returns, irrespective of market sentiment. Investing on auto-pilot - cutting out the noise, and focus on the long-term prize.

Very interesting Harvia stats at the end! Grazie