When ROIC is a Flawed Metric - 5 Scenarios (and Examples)

ROIC is much more nuanced than most investors realize

Introduction

Return on Invested Capital is one of the most important metrics to assess a company’s capital efficiency and effectiveness of reinvestments.

Notwithstanding the obvious conclusions one can draw from ROIC (the higher the better, is it above-average, does the company have reinvestment opportunities), this ratio is being generalized too often in the investment community.

It’s much more nuanced than putting up a percentage from which we then must deduce whether the company is a compounder or not. Let’s talk about 5 scenarios under which ROIC is flawed and how we should incorporate them into our analysis processes. We’ll present practical examples, highlight more cases in the upcoming webinar(s) and share one of our favorite stocks (at the end of this post).

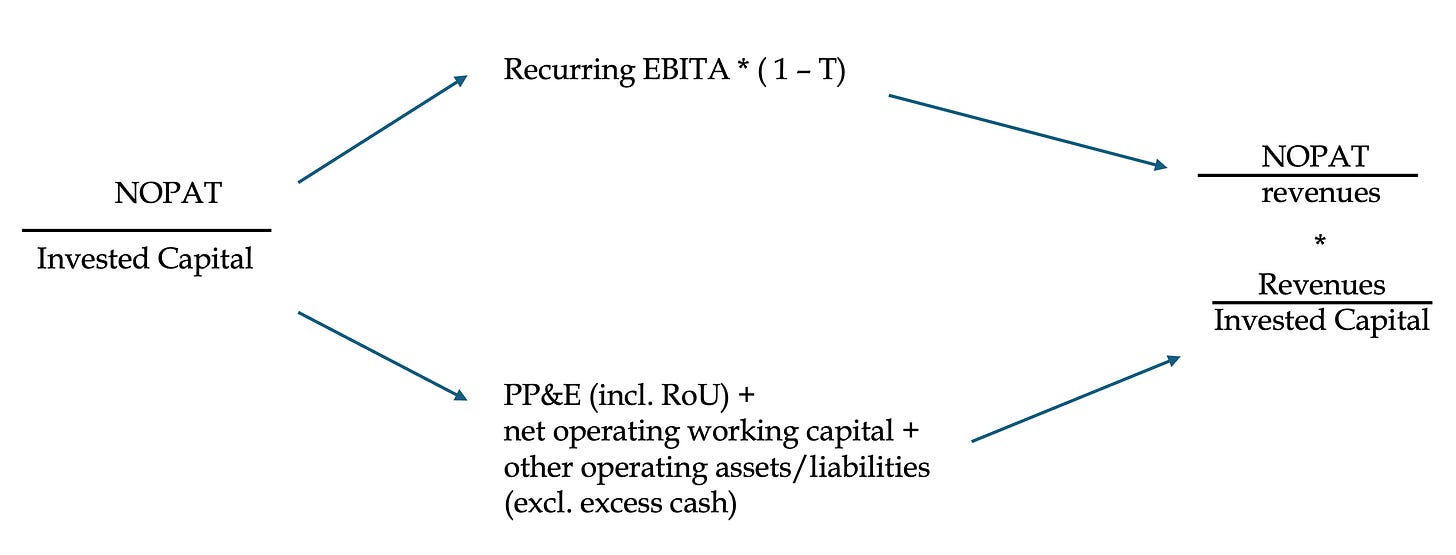

The below scheme could serve as a quick refresher.

NOPAT = recurring EBITA * (1 - tax rate). We view NOPAT as the steady cash flow excl. depreciation related to growth investments. NOPAT must be based solely on recurring maintenance CAPEX (i.e. D&A in a steady-state situation). The last thing we want to do is penalize companies that are investing for very profitable future growth. For a double-digit ROIC company, one-off growth CAPEX in durable long-life assets (modern plants, state-of-the-art machinery) are likely to be highly rewarding in the long run.

Invested capital = generally PP&E + net operating working capital + other operating assets/liabilities.

As shared on the “About’ page, we approach long-term public stock investments the same way we research private M&A deals. To us, good companies should have the quantitative following tenets:

Strong ROIC with decent reinvestment opportunities

Good ROIC when the business is still scaling

Low maintenance CAPEX relative to EBITDA, adjusted for capitalized development costs

Strong utilization rate

Low or preferrably even negative working capital

The latter is under-appreciated, especially during times of higher inflation and/or supply chain constraints. Working capital management is key to reinvesting cash flow continuously. We like companies that fully exploit their existing network by searching for growth avenues that require little or no CAPEX.

What about the strong utilization rate? Recognizing that every company has some sort of cyclicality, we want to minimize the risks of investing in companies with low utilization rates. It makes the ROIC and reinvestment modeling more complicated.

Ultimately, companies should maximize IRR on their growth investments: we want a safe and relatively fast payback. When there’s too much supply, growth investments won’t generate sufficient future cash flow relative to the required rate of return.

Let’s jump right into 5 scenarios under which reported ROIC is oftentimes flawed. And there’s no right or wrong here: ROIC constantly changes and it depends on the nominators and denominators you’re utilizing.

1) Timing of growth investments impacts ROIC

Clearly, the timing of executing growth investments can make ROIC more volatile. We found this to be the case especially for smaller-sized companies that are still ramping up production (capacity). There’s no way assets under construction (e.g. plant extension which oftentimes takes multiple years to finalize) can contribute to the overall NOPAT. Nonetheless, those investments have already been registered on the asset side, resulting in a lower ROIC. It takes time to fully ramp up those investments and for them to reach total group ROIC.

Consider the below example: investments for future growth that will drive strong NOPAT growth (based on maintenance CAPEX) but initially suppress ROIC. Eventually, incremental and total ROIC will have grown considerably over a 5-year span. Conclusion: (reported) ROIC changes constantly.

2) Taking an average ROIC to above-average: not impossible

Old Dominion Freight Line, O’Reilly Automotive and some of the other greatest compounders of all time started out as lower-ROIC businesses. It took them multiple decades to triple or even quadruple their starting ROIC. At first sight, a 10% to 12% ROIC doesn’t seem enticing but we shouldn’t jump too fast to a potentially wrong conclusion. While we acknowledge the low and high ROIC persistence, there are exceptions to this rule.

ODFL operates within a fragmented sector (less-than-truckload shipments) and learned how it could take advantage of its competitors’ structurally underinvested situation: doing things the other way around. Leveraging the existing network, investing heavily into new capacity, reducing the operating ratio and maintaining a strong balance sheet... Because of ODFL’s excellent service (on-time deliveries), competitors have so far failed to reciprocate effectively.

ODFL definitely understands how to sustain the compounding flywheel. Back in 2013, it posted a reported 12% ROIC which had already grown to 20% by 2018. Today, it’s closer to 26% - 30%. In FY13, net profit margin was 8.8% versus today’s 21.5%. Stated differently, driving profitability by enhancing the overall service level has been key to more than doubling ROIC.

What are the required annual maintenance CAPEX? Hard to figure those out exactly, but including the small portion of lease renewals they should be something like 2.5% of total revenues. In FY23, D&A made up 5.5% of total revenues as higher D&A is linked to - not so surprisingly - growth investments.

Another company that’s managed to dramatically improve existing network density and profitability since 2018: Linde Plc. Total invested capital has remained relatively flat and shows how Linde is more of a tolling company: fixed payment contracts regardless of production levels. So the total ROIC doesn’t reflect the future returns on new, more CAPEX-growth related investments (like those to support the energy transition).

Also: ROIC is partly based on working capital efficiency. Let's say a company isn't growing revenues, NOPAT and doesn't invest in future growth but it succeeds at reducing working capital: ROIC goes up, but that's a one-off (and a one-off cash inflow). So the composition of invested capital should also be contextualized.

In 2022, CFO Matthew White summarized it as follows:

And the obvious answer is we're growing earnings faster than our capital base, but I think the underlying thing to take into consideration is we are less capital intensive than I think people realize. We have a lot of avenues of growth that don't require significant capital. We're demonstrating that through our end markets. We're demonstrating that through our supply modes of package and some of the other services we have, and we see a continued opportunity to see expansion of return on capital through significant growth that does not require significant capital.

As mentioned above: we want companies that maximize IRR on growth investment while keeping the aggregate ROIC at high levels. As long as the investment returns exceed the hurdle rate and the weighted average cost of capital, companies should embark on every possible growth opportunity while at the same time making sure it’s funded properly.

And exactly, to start off, IRR is the primary criteria for incremental investment decisions and ROC, as you know is the – basically the accounting metric on the back end. And when you think about where ROC has been and as Sanjiv mentioned in the prepared remarks, we believe that maintaining an industry-leading and healthy ROC and operating margin while growing EPS, while growing OCF is the best combination for shareholder value creation and ultimately, relative TSR outperformance. So, while they are of course at theoretical limits, 25% we think is a healthy number. Obviously, the pricing has helped the non-capital intensity of our growth. We are embarking on a more capital-intensive growth as we look out on some of the energy transformation and we see that as good growth. It meets our investment criteria. So therefore, I would see the ROC number, yes, plateauing now as it is, maybe even declining a little bit. But we view that okay as long as we continue to make the right decisions on IRR which we feel very confident about. So for us, it’s more about maintaining healthy levels and maintaining leading levels while growing the organization. But we are not going to let those metrics as either operating margin or ROC inhibit our decisions for good growth projects, they never will.

3) ROIC is based on book value

There you have it: book value (gross value minus depreciations) versus actual replacement cost. It’s clear that new reinvestments are linked to today’s inflation: i.e. the new-build construction cost of a new plant, machinery, equipment, vehicles et al. To put it simply, we’re not interested in the acquisition cost of 1998: we’re living in 2024.

When companies are inefficient (lower utilization rate), and subsequently face a decrease in revenues, maintenance CAPEX is likely to get cut in absolute terms. However, corresponding maintenance D&A is linked to the previous years’ maintenance CAPEX spending pattern. In the long run, assuming a steady-state going concern, maintenance D&A equal maintenance CAPEX and lease renewals. Also, maintenance CAPEX spending can be optimized: choosing the latest and most efficient equipment that lasts longer leads to. a higher upfront investment but higher production IRR (i.e. longer expected useful economic life).

Let’s review a hypothetical situation: starting a new company in 2024 with the plant and all equipment operative from January 1, 2024.

Reported ROIC = EBIT x (1 - tax rate) divided by reported invested capital at book value

ROI (incl. tax benefit from growth D&A) = NOPAT (EBITDA - D&A related to maintenance CAPEX x (1 - tax rate)) + growth D&A * 25% (tax benefit) divided by total invested capital at historical cost

Straight-line depreciation: 30 years for plant and other related investments, 6 years for machinery and equipment and other related investments

In fact, ROI is similar to Constellation Software’s measure for ROIC on acquisitions

What we’d want to highlight: from FY30 till FY32, this company reported an increase in reported ROIC despite flat revenues and EBITDA, because of total D&A exceeding total CAPEX. That doesn’t make any sense.

The adjusted ROI shows why it’s better not to take a reported ROIC figure at face value. ROI (could be reduced by 2 pp to reflect inflationary pressures) is a better indicator of underlying performance: it’s based on utilization rate, it’s not affected by a slowly decreasing reported invested capital figure, it’s driven by current profitability. Also, objectively calculating how much capital will be tied up in order to grow NOPAT by x % should be easier (when all capacity is being fully utilized).

4) Capitalized development costs

Capitalizing R&D is classifying a research and development activity as an asset rather than an expense. When you capitalize development costs, you’re increasing EBITDA, EBITA and NOPAT. Of course, R&D capitalization also transfers the costs from the P&L statements to the balance sheets by representing them as assets.

This has huge implications for ROIC, also for one of our portfolio holdings. Excluding capitalized development costs, ROIC is much higher than reported.