Will Our Quality Growth Companies Revert to the Mean?

Thoughts on ROIC, growth, and how it impacts valuation

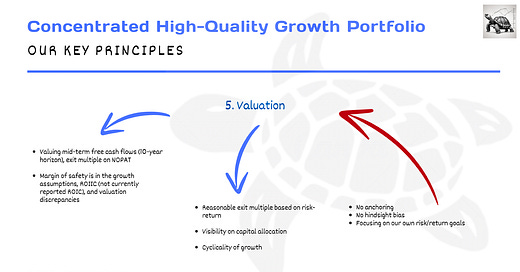

Setting an Exit Multiple

Yesterday, we received an interesting remark on our Lifco deep dive as it relates to the base case valuation model, stating that picking a 20x NOPAT exit rate is merely speculating on the company’s run-rate valuation and neglecting the impact of diminishing ROICs.

I have always struggled with DCFs because of the terminal value. A multiple of 20 should be translated in the time period of excess return of the franchise. After this period the business merely earns its cost of capital. Otherwise, a multiple of 15 or 25 could also be used… No one knows exactly, but the excess return period assumption should be realistic. Using the past multiple of 20 is not calculating an intrinsic value, but a speculation on the market price in my humble opinion.

It’s good to receive this kind of critical questions: our Substack isn’t one way street; it’s about engaging with others and challenging our thought-process. No anchoring, but maintaining an open-minded view on our portfolio strategy.

That’s what we’ve shared in yesterday’s webinar as well.

First off, determining valuation is highly subjective, and it’s not black or white. It’s about understanding a company’s longevity (relative to direct peers) and weighing alternative investments of equal quality (relative to a minimum risk-free rate) to justify a certain exit multiple. Truly exceptional business deserve a premium valuation, just as long as it’s not excessive.

There are analysts who use a DCF, a reverse DCF, and others who put a one-year multiple on their current FY’s EPS. We take a common sense approach of ROIIC, reinvestment, excess free cash flow and an exit multiple, and calculating the implied rate of return adjusted for dividend withholding taxes and other real-life headwinds.

Optionality plays a key role in our valuation process: what if the company reinvests more at very attractive ROIICs or what if valuation normalizes faster than anticipated? That efficient growth component relative to competitors is what we believe makes our companies relatively inexpensive from a longer-term point of view.

Avoiding Indecisiveness

If a stock is able to produce solid risk-adjusted returns, we’ll buy it. We don’t want to overthink currently fair valuations too much, as it could lead to indecisiveness or a migration toward deep value stocks that are only likely to make you money if there’s an event (turnaround or the opportunity to buy them at cheap valuations, e.g. COVID-19). But as we stated multiple times already, many (if not all) investors don’t buy into a position all at once. Therefore, picking cheap stocks is highly timing sensitive.

Mean Reversion

In our view, a traditional DCF approach has several flaws. First, it focuses on calculating a relatively short-term price target, which can encourage over-trading—selling or trimming positions once the target is reached and then seeking other opportunities. The real crux, however, lies in the assumption of mean reversion of ROIC towards the WACC or hurdle rate, as we've emphasized in the above question.

The key question is whether our quality growth companies will experience mean reversion, and if so, on which metrics. In other words, how will changes in these variables ultimately impact their valuation? It’s too easy to state that company X with a 25% ROIIC, 35% reported ROIC and industry-leading margins and revenue growth will mean-revert, and hence, it should be trading at market-average multiples.

As a side-note: rather than debating on the multiple, we’ve seen many investors use the wrong assumptions on ROIIC, thinking it’s just the currently reported ROIC. That's entirely off the mark, as it overlooks the impact of inflation and how invested capital is structured—whether in working capital or fixed assets. It also fails to consider how purchase price accounting for M&A is handled, such as the distinction between goodwill and amortized acquisition-related intangibles.